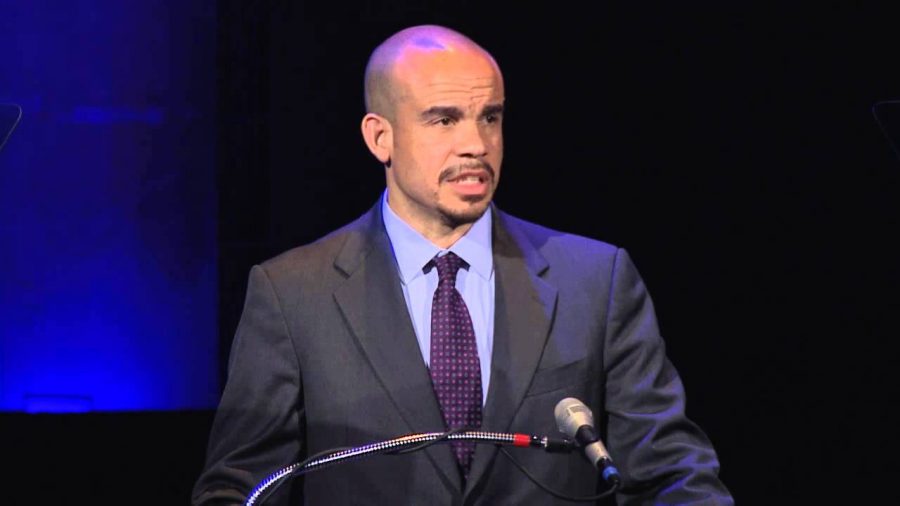

Josh Edelman: A Feature

February 5, 2021

One by one we filter onto the call. Each classmate’s face appears in the square box on the Zoom screen. Several of us are clutching our coffee cups, two are messing with their hair, and one is straightening his collar. We have about ten minutes for last-minute preparations. “I’ll start with introductions,” says one classmate. “And I’ll begin with the questioning,” says another. In an online school culture in which most school groups look like a menagerie of emojis, we have a habit of greeting each other with bright eyes and happy hellos. This will be our first interview of the school year; we have designed and organized our questions, and we have done the research to learn about our interviewee.

In Josh Edelman’s career, he has served as an educator, mentor, and principal to students in Washington D.C, Massachusetts, California, and Chicago. He earned his Bachelor’s degree in American history from Harvard University and two Master’s degrees in education and educational administration from Stanford University. As a social studies teacher for ten years, he encouraged students to trust their innate brilliance and strive to reach their fullest potentials, and as a principal, he took on school-wide responsibilities and helped children and teens “make sense of the world.” Edelman served as the principal of the SEED (Seeking Educational Equity and Diversity) Public Charter School of Washington DC and then Academic Program Advisor to the SEED Foundation, a role in which he worked to close the achievement gaps of low-income students by ensuring a supportive and nurturing environment. He founded RISE (Realizing Intellect through Self-Empowerment), an initiative to support African-American youth. Edelman then became the Executive Officer of the Office of New Schools in Chicago and later served as the Deputy Chief of School Innovation for DC Public Schools.

During our pre-interview meetings, we discussed his career path and shared information we learned about his life and celebrated parents. We imagined his childhood dinner conversations, how they must have influenced his philosophies and value system. Josh Edelman is the oldest son of distinguished parents: Marian Wright Edelman, counsel for The Poor People’s Campaign, a Civil Rights activist alongside Dr. Martin Luther King, and the founder and President Emerita of the Children’s Defense Fund, and Peter Edelman, a former Legislative Assistant to Senator Robert Kennedy, a law professor at Georgetown University and an author of books about poverty, welfare, and juvenile justice. Marian Wright Edelman and Peter Edelman, now in their 80s, met and fell in love when they were young lawyers working for King and Kennedy, who were both assassinated in 1968. Josh’s parents wed in July of that same year; it was an interracial marriage of a Jewish man and an African American woman. Despite his parents’ impact on the world, the interview would reveal to us that to Josh Edelman, they are simply mom and dad, the parents who taught him and his two younger brothers, Jonah and Ezra, about the importance of using privilege to lift others up and create lasting change.

A minute before “go time,” Josh Edelman arrives and with his appearance, our faces are jettisoned to new positions on the screen. A smiling man with lighthearted energy that emanates joy has joined our abbreviated checkerboard. One by one we introduce ourselves, and within minutes it is evident this interview will play out less like a formal interview and more like a kick your feet up roundtable talk. Edelman is authentic; there are no pretenses or falsehoods.

We ask a poignant question. “Have you ever faced discrimination?” He nods and launches into a story about seventh-grade math. It was the early 1980s, and he had just transferred from a public school – where he had excelled in math – to an elite DC private school. Due to his high testing scores, he was placed in an advanced algebra class, and by the end of that school year, Edelman had a B minus average. The school administrators said, “Hey, you know, you’re new; it’s hard here, why don’t you take the same class again in eighth grade.” He went home and shared the message with his parents, who said, “OK, sure.” So he took the same class again in eighth grade and got an A without much effort. Edelman adds “[he] was intimidated as a new seventh-grade student in the school, and [he] was in a class with all these big eighth graders.” Teachers are cognizant of this, or they should be. Right? The mostly white instructors and student body advised him to re-enroll in the same class the following year, without justification. He did not consider protesting because compliance “seemed the thing to do.” The following year, as a nascent high school student, again they approached him saying, “High school’s hard here, so there’s two math tracks you can be on… the track that takes you to pre-calc, or the track that takes you through calculus BC. Well, you should probably just take the pre-calc track.” Again, Josh answered them. “OK.”

Edelman makes it clear he brings up this story to point out these educators “thought they were doing the right thing, but this was dysfunctional racism. This was them making a decision – that I could or couldn’t do something – on my behalf because of the way I looked in this setting… nobody was malicious; nobody was ever mean to me, but they were making assumptions about what I could and could not do.”

The issue of racism in the classroom is not one Edelman faces alone. In Moyers on Democracy, Steven Hseih’s article explores statistics on racial inequality in the American school system. Black students are expelled at three times the rate of white students and many schools with high populations of students of color are less likely to have access to a full range of courses or fully qualified teachers. Even at the preschool level, black students account for 18 percent of pre-K enrollment, but makeup 48 percent of preschoolers with multiple out-of-school suspensions.

Edelman reflects as both a teacher and a principal, saying “[my middle school experience] has driven me as a professional to realize we cannot judge young people, or adults [for] that matter, based on the way that they look, where they live, how they talk, or what they might aspire to.”

In 2011, Edelman joined the educational initiatives at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, providing grants and funding to well-deserved projects. According to the foundation, Edelman’s team, composed of mainly Black and Latinx people, works to provide funding and support to significantly increase the number of Black, Latinx, and low-income students earning diplomas, enrolling in postsecondary institutions, and obtaining credentials with labor-market value.

Edelman’s influence extends beyond the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation into his home, where he is the father to two girls, Ellika and Zoe. Edelman instills in them a drive to create change, as his parents did for him and his two brothers. As his younger daughter moves away from high school and into college, Edelman looks to his own future. He is not sure what lies ahead, but he aspires to further collaborate with people across the sectors of housing, employment, and poverty for the betterment of young people across the county.

Toward the end of the interview, Edelman reflected on his career as both a teacher and a principal. His compassion for others is palpable. For him, it’s about forging connections and inspiring others. “The joy that comes from [my work], although not in the moment … 20 years in the future you know it’ll be worth it … I hope they’re happy people, I hope they’re people that are doing good things.”